As a high school student, the extracurricular landscape often feels less like a place of discovery and more like a battleground for college applications.

In joining a club or picking up a new activity, students are also trying to further their resumes and impress the admissions officers at colleges. It is not about what brings them joy or fulfillment—it is about reaching ten extracurriculars on the Common Application (Common App).

Of course, extracurriculars do matter. College admissions officers want to see leadership, passion and commitment outside of just pure academics, grades and GPAs.

But somewhere along the way, the original point of extracurriculars—self-improvement, exploration and even fun—seems to have been diluted. Instead, students pick up hobbies they do not care about, founding clubs they have no intention of actually running and attending meetings just long enough to get their names on the roster.

William Deresiewicz, in his book Excellent Sheep; a book that is a part of the curriculum for AP English Language and Composition; describes how top performing students are so caught up in the chase for an ideal college application that they rarely stop to think about what they truly want. They craft resumes rather than lives, checking off the boxes of leadership, service and research without any real authenticity. They are not forming clubs because they are fascinated by a subject or dedicated to a cause. They are doing it because “President of X Club” looks good on an application.

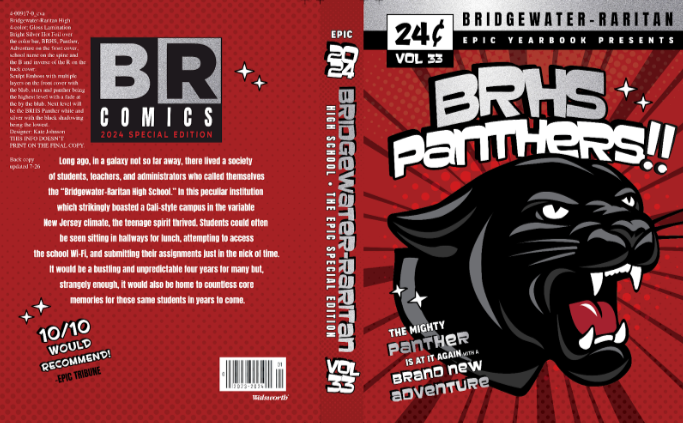

Take, for example, the number of new clubs that are created each year at our school. It is not that the student body has suddenly become passionate about five new niche interests, even if the caliber of students may be increasing year-on-year. It is that ambitious students have realized that starting a club is an easy way to gain leadership experience, never mind that the club only meets twice a year, or if its only real members, or worse, the entire officer board, are the president’s friend group.

There are also sports and volunteer programs that students participate in just for the sake of participation. Some students commit to varsity teams because it rounds out their application, not because they love the game. Others sign up for community service projects they have no real connection to, just to gain hours. And when asked about these experiences in interviews or essays, they carefully craft narratives about how they were “deeply moved” or “forever changed” when, in reality, they were mostly checking a box.

It is not that these students are inherently dishonest people. Rather, it is that the system itself rewards performative passion over the real thing. Colleges do not want students who dabble to find their true interests; they want commitment, consistency and leadership.

So students, in an effort to be exactly what colleges want, shape their lives accordingly. Deresiewicz argues that this pressure leaves students intellectually and emotionally stunted. Instead of exploring who they are, they become “excellent sheep.” High-achieving, disciplined and successful students but without any real sense of purpose beyond the next step in their high school or college careers.

What is lost in all of this is the joy of learning, the excitement of discovery and the freedom to explore interests without the shadow of college admissions looming overhead. When everything is a means to an end, it becomes nearly impossible to engage in anything simply for the sake of personal growth.

But what if we did things just because we loved them?

What if someone volunteered at an animal shelter because they actually cared about animals, not because they needed 100 service hours? What if someone joined a club because they truly enjoyed it, not because they needed a leadership title? What if extracurriculars were about becoming a better, more interesting, more curious person—not just a better applicant?

In short, many students may take an approach that sees their extracurriculars built around college applications, and it is hard to blame them for wanting to prioritize their future. But if we are going to spend four years shaping our lives around extracurriculars, should we not at least be doing things that make us happy?

Dora C • Apr 9, 2025 at 2:05 pm

Yes! This! BRHS has so many electives and clubs; students should be encouraged to dabble in as many of them as they’d like. The idea of “checking the box” for college applications is definitely doing kids a disservice.

Arun Kakarla • Apr 9, 2025 at 11:27 am

Very well written and nicely thought!!!